David Lee: A Life in Plants

Many people, activities and institutions, particularly while growing up, strongly influenced my development as a plant biologist and university professor. At different stages of my career I have reflected on those influences, but now I have now finished my formal work as a scientist and professor and especially welcome the opportunity to reflect on my life. Writing this chapter is an opportunity to do just that, contemplating with more than the usual focus and discipline, easy to skip in the normal day to day activities, even in retirement. Writing it also gives me another opportunity to honor those individuals who helped me along the way, and adds to my feelings of humility and gratitude.

CHILDHOOD

I was born and grew up on the Columbia Plateau of Washington State. My mother and father, John and Mary Lee, moved to the small town of Ephrata, which was the seat of Grant County, recently married and starting a new life together. My mother’s family was originally from Seattle, but moved frequently in the state following the work of my grandfather as a civil engineer. She came from English and German background, from ancestors who lived in Pennsylvania in the early 19th century. My father’s family moved to the town of Chelan, from Michigan and Illinois, in 1920. I was told that we came from the Lees of Virginia, but genealogical research by a distant relative indicates that our ancestor,William Lee, arrived in New York around 1675. A look at my family tree shows the good and bad sides typical of a family; a family name is Webster (my middle name) after Noah Webster, another family name is Hawkins (my dad’s middle name) after the notorious pirate. My father’s family moved to the town of Chelan, from Michigan and Illinois, in 1920. My grandfather practiced dentistry and was unsuccessful in starting an orchard.

Both families moved to Grand Coulee to find work associated with the dam construction in 1933, and my mom and dad met there. My father came to know Jim O’Sullivan, who was an early booster of the dam and associated irrigation project (for which Ephrata became the headquarters). Dad ran a small luncheonette near the movie theater in Grand Coulee, and he noticed that people could find the money to escape to the fantasy of movies, even in the depths of the great depression. So they moved to Ephrata, purchased and renovated the local movie house, the “Kam” renamed the “Capital”, and started the “sagebrush circuit”, showing movies in grange halls in the small dry land farming communities in the area. The business prospered, and my parents eventually owned and ran a chain of some twenty theaters and drive inns in that part of the state, the Columbia Basin Theaters.

I was born in Wenatchee, the largest nearby city, in December of 1942; there was no hospital in Ephrata until three years later (and my father was instrumental in its establishment).

I grew up in this little town, in a small house, later enlarged, on the edge of town, Ephrata was an isolated but progressive place in the middle of the sagebrush steppe (or cold desert) of the Columbia Plateau. It served outlying agricultural activity and consisted of retail business, support of the Great Northern Railway (including a row of grain elevators), county government employees, and the skilled professionals who designed the Columbia Basin Project, one of the largest irrigation projects in American history. Ephrata was known for its excellent school system, and the town was like an oasis in a harsh treeless landscape. As a child, I had a bicycle and the means to travel anywhere in town, as well as into the dry washes (alive with salamanders and frogs in the spring time) in the countryside. During the summer months, my friends and I would spend entire days together away from our homes and families. The landscape, with the Grand Coulee just north of town, was a powerful presence: blue cloudless summer skies, hot days and cold nights, dark basalt canyon walls with flecks of lime green and orange lichens, and mineral-rich lakes on the canyon floors. As a child, I did not have any real mentors leading me towards a career in biology, but was strongly influenced by my personal experiences in nature with my friends.

There were some strong themes in my childhood, associated with the institutions that were in the town and prepared children for adulthood. These institutions were the schools and the churches, and organizations for children and youth: cub and boy scouts, girl scouts, and Future Farmers of America.

I was the middle child, with an older brother and younger sister. There were fights among us kids, but we got along pretty well and stay in contact with each other today. It was a stable family situation. My mother took care of the home and family, and also helped my dad with financial aspects of his business. My father worked hard to make his businesses successful and that made him a little remote from us. He also performed a lot of volunteering in the community. He was the first president of the hospital association and a leader of the Lions Club campaign to raise funds for the first local hospital. He was active in the Lions, serving as chapter president when they built the first park and swimming pool. My mother and father also were active in the concert association, which brought performing artists to Ephrata, with concerts in the Lee Theater. Eventually, my dad served on the city council, and then served as mayor. Neither of my parents completed college; my mother went to a business school for a few months, and my father attended the University of Washington for two years before his money ran out. At 21, he was running a small mercantile and dry cleaning business, with two stores. By 23, after the beginning of the Depression, he was bankrupt. Despite his business background, he was a lifelong Roosevelt Democrat. My parents often joked that their votes cancelled each other. Education was important in the family, and each of the three kids graduated from college.

David Lee, at the age of 8 (1950) on the shores of Blue Lake, about 25 miles north of Ephrata in the Grand Coulee. My sister Mary Ann is on the right, and my mother Mary is on the left. I learned to swim at this beach.

I attended the public schools in Ephrata, first Parkway Elementary, just a half block from our house (and I was frequently observed still polishing off the remains of my breakfast while walking into my classroom!). Then I attended junior and senior high school at the north end of the town. Early in the third grade, our teacher, Miss Storm, took the children to the town library. We were allowed to check out a single book. Mine was about a Dutch child who stuck his finger in the dike and held back the flood waters to save his town. It sounds pretty stale now, but it was a revelation, that a book could open up a new world to me. From that time on, I read voraciously. In the fourth grade, with crowded schools, my classroom was the Parkway School Library. I remember reading Raymond Ditmars Snakes of the World, and Reptiles of the World, which I discovered on the library shelves. By the end of the fourth grade I read books at an adult level. I read widely, but particularly enjoyed mystery novels for kids and science fiction. A notable aspect of my childhood, even fairly unusual in our town, was the absence of television in our household, until my senior year of high school. TV came to Spokane around 1950 and could be picked up in Ephrata with a high antenna, but my father refused to own a set for many years; TV was the single biggest threat to his movie business. However, in those days we had two movie houses owned by my dad, the Marjo (short for Mary and Johnny) and the premier Lee Theater, with two changes of double bills per week plus the Saturday afternoon kids’ matinee—so I saw 4-5 movies every week.

I was not a great student, and was even a pest in junior high school. When I began to take studies more seriously, in high school, I did not excel. In my graduating class, and I am still friends with many of my classmates, I was a “B” student; some of my friends were quite bright and later attended some prestigious universities, including MIT, Yale, The Air Force Academy, and Cal Tech. I took the normal pre-college curriculum of Biology, Chemistry, Physics, a language (French), pre-college English, and pre-calculus mathematics. I had some notable teachers during that time. Mr. Bob McIntee was a well-trained and excellent chemistry instructor, and very enthusiastic about science. Mr. Bob Atkinson, who was also my basketball coach, taught world affairs and very carefully included a unit on Marxism (unusual during those times of McCarthyism). I had excellent English language instruction. My senior instructor, Miss Gerhardstein, was a literature Ph.D. candidate at the University of Washington. My writing was good enough for me to win the writing award for my class during graduation, but that was partly the result of the awards being spread around. Otherwise, Larry Reeker who finished Yale in three years and became a respected expert in artificial intelligence, would have one all of the awards.

An important activity for kids growing up in Ephrata (as in all towns in our region) was sports. I had some older neighbors who had excelled in high school sports, whom I idolized. My brother, three years older than I, was active in football, basketball and track, and I followed his footsteps in those sports. I was a bit over-weight in junior high school, and didn’t begin to have much success until the 9th grade, when I grew several inches. At 6’ 2 1/2” and 185 pounds, I was the tallest of the athletes at Ephrata High School—the Ephrata Tigers. I played end on offense and defense in football, center on the basketball team, and ran hurdles, 220 yard dash, and even competed in high jump for the track team. I played those sports for three years, and lettered my junior and senior years—was the captain on the football and basketball teams. I was very serious about sports, and from that participation I learned much about effort, focus, patience, endurance, and teamwork. These were qualities that later became important in graduate school and my career in scientific research. During that career I saw many colleagues, who I gauged as much brighter than I, fall by the wayside for lack of those qualities.

As all small towns in the region, Ephrata was a religious town, with far more churches than taverns, and lots of protestant denominations. The one family with Jewish cultural roots, the Agronoffs, eventually became Episcopalians. My family was not particularly religious, and we did not belong to any denomination when I was a young child. However, we shared a backyard boundary with a young Lutheran Minister, Ray Pfleuger (“Pastor Ray”), and he frequently was invited for dinner. He established a congregation, and the church was constructed in our neighborhood, so our family became Lutherans (of the more progressive ALC variety). I was baptized in this church when I was about 10 years old, and was confirmed in the church at 13. I had many deep questions about death and the immensity of the universe (which was easy to imagine from the star-filled skies above our town), and got a little comfort from Christian devotion….for a while.

Close high school friends, taking a break on the high ridge above Deep Lake in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness of the North Cascades, 1961. Left to right: Curt Amo, Alan Lindh and John Freer.

I had many experiences in nature, both near the town and further afield, growing up. As a child, I was active in the Scouts. In Boy Scouts, we had a great troop leader, who organized camping trips on the Columbia Plateau and in the Cascades. I have vivid memories of the places we visited. However, a new troop leader took over, insisted on treating us like little soldiers, and I quickly left. During the summers, many from my town went to the Lake Wenatchee YMCA Camp, deep in the Cascades and along the shore of Lake Wenatchee. I first was a camper for many years, and then helped out in the kitchen and as an assistant counselor as a young adolescent. My experiences at the camp, hiking and studying nature, deeply affected me. The YMCA movement had a religious/ethical program installed at these camps that combined Christianity and native American reverence for nature. The programs involved accepting a challenge of behaving nobly and receiving a bandana (in colors denoting different stages) in a sacred ceremony. It had a profound effect on me, much more than learning the tenants of Lutheranism. My father was a very busy man, but he did take my older brother Jack and me on fishing trips, as up the Sanpoil River, and on a long trip up the Alaskan Highway to Fairbanks. We drove up on an old Dodge truck with a heavy canvas cover on the bed and side stakes—and three bunk beds. We came back with a booth of movie projection equipment he’d bought from the Air Force on auction. We stopped to sit in hot springs and fished for lake trout and grayling. I grew up a lot during that trip. We also took some family vacations, as to the Oregon coast and Glacier and Mt. Rainier National Parks, which exposed me to the beauty of those sublime landscapes.

I was part of a close group of friends, first as a child and then as an adolescent during the high school years. We talked about all sorts of topics, including the existence of evil, free will, time in the universe, utopias, and on. As we began to drive (a few owned old cars) we went on back packing trips into the High Cascades Mountains, to the west. Often, we’d hike up over a mountain pass to a high lake on Friday evenings, using carbide miners’ lamps to light the way, and then return on Sunday afternoon. Occasionally the trips were a bit longer. The scenery was majestic, and inspired our conversations about the nature of the universe.

I worked summers in an aluminum fabricating business my father had started, manufacturing and installing commercial and storm windows and doors. I learned how to use many tools, including welding aluminum. This experience was invaluable in giving me some manual skills that were important to me later on in scientific research.

COLLEGE YEARS

I graduated from Ephrata High School in spring of 1961. All of my friends were bent on attending college, and so was I. I had written a letter to the Chairperson of the Botany Department at Washington State University, asking questions about carnivorous plants. He had sent a long typewritten letter in reply, very impressive to me—and it was natural for me to be interested in attending Washington State. However, I had attended a senior open house weekend, and all of the students were drunk. It didn’t seem like the place for me. In my junior year, I had been selected as a delegate to attend Boys State, which was held on the campus of Pacific Lutheran University, just south of Tacoma. I was leaning towards studying biology, and PLU had a good reputation in the sciences, so I decided to attend there. It was a good place for me, with small classes and a couple of inspiring teachers.

My freshman year I took Zoology I and II, taught by a parasitologist, Prof. Keith Strunk. This rigorous course (and I found the parasite life cycles fascinating) was the portal for the selection of pre-med students, and Prof. Strunk was their mentor. I received a high “A” and was invited to an interview with this iconic figure. When I told him that I was thinking about studying plants and certainly not medicine, a look of incredulity and disgust took over his face and the interview was cut short. I had excellent chemical background from high school and was invited to take an experimental general course, with Dr. William Giddings, a recent Harvard Ph.D., in which I spent much of my time devising experiments; it was a great entry into science and the scientific method. Most impressive among the biologists was Jens Knudsen, who was a zoologist with a love for nature and teaching, and a research program in marine invertebrates. The summer of my sophomore year, I attended a field course taught by Dr. Knudsen and his colleague Dr. Harold Leraas, a very kind elderly man, at Holden Village, high in the Cascades off of Lake Chelan. Holden Village was an old mining town converted into a Lutheran retreat site, on the edge of the Glacier Peak Wilderness and accessed by road from a remote landing on the lake. We had lectures, but spent much of our time hiking and camping in the high cascades, learning the plants and ecology as we travelled.

PLU was a liberal arts institution, and I benefited much from a variety of courses: British Empirical Philosophy with Curtis Huber and George Arbaugh, Asian History by Walter Schnackenberg, and American literature by Martin Hillger, among others. I retain an interest in these subjects to this day.

I did not return to school the fall of 1963. I was having some emotional problems; I was quite immature really, and decided to give myself some time for work and travel. This was also a time of religious yearning, not met by any experiences in Christianity, and I was reading theology: Bergson, Teilhard de Chardin, The Varieties of Religious Experience, and more. I found a job at the Weyerhaeuser Paper Mill in Longview, along the Columbia River and downstream from Portland. I found a room in a boarding house and hitch-hiked to my job at the mill. It was shift work, and I could make pretty good money during holidays with overtime. I saved most of my earnings, preparing for a trip to the South Pacific, mainly New Zealand. I wanted to visit places with great natural beauty, so this trip was definitely more attractive to me than studying in Europe, as several of my college friends did. I quit the mill in January, and boarded the S.S. Oronsay in Vancouver for an 18-day voyage to Auckland. We had layovers in San Francisco, Long Beach, Honolulu, and Suva (Fiji Islands). Several of us took advantage of these stops to visit areas away from the port. Arriving in Auckland, New Zealand, I soon got on the road, hitch-hiking up and down the North Island, down the South Island, even to Stewart Island. I saw much of the great scenic beauty of this island nation, and also studied botany and zoology for one term at Victoria University of Wellington. I left in July, flying to the Fiji Islands and Society Islands, then Hawaii, on my way back to the U.S. In Fiji, I travelled up to a hill station on the largest island, Vita Levu, and ascended the highest peak, looking for the famous Degeneria tree (thought to be the most primitive angiosperm at the time). I didn’t find it, but travelled through a magical cloud forest to the summit and enjoyed a Kava ceremony with some elders in a nearby village. After my return, a young British couple who were volunteering as foresters, invited me for tea. They said to me, “you can do what we’re doing.” They made a great impression on me, and I decided to become a botanist and study plants in different parts of the world, helping people along the way. I wasn’t sure how one did this, but knew I had to study plants in earnest.

I had many opportunities to travel in mountain wilderness areas as a college student, both in New Zealand and in Washington State, and experiences during some of those sojourns were transformative. In July of 1962, I hiked up the Surprise Creek Trail in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness Area, and then joined the Pacific Crest trail to switch back up onto the ridge above Trap Lake. Just north of the trail on the ridge crest was a boggy area with low mounds of sphagnum moss amidst the subalpine setting and wildflowers. Time stopped, the vegetation began to glow with its own light, Glacier Peak beckoned to the north, and I was transformed. In April of 1964, I hitchhiked to the end of the road on the west coast of the South Island. Then I followed trails set up by surveyors (a highway now traverses the area) towards the road terminus to the south). It was late in the day. There were several trails and I got lost. Then it began to rain. And I became ecstatic; time stopped and the setting became luminous. Eventually, I found my way to the terminus and stayed the night in an abandoned house, and the memory of that experience stays with me now, just over a half a century later. These powerful experiences added to my motivation to study plants and do research in nature, a big part of the mix of motivations that led me to become a professional botanist.

So, I returned to study at PLU, finishing my science requirements and took the plant courses that were offered. I wanted to do a research project, and the physiology professor, Earl Gerheim, suggested that I start a project studying evolution by comparing the proteins of plants using immunological techniques, techniques he knew something about. I had been struck by the beauty of members of the heather family (Ericaceae) in my studies in the Cascades the previous year, and then saw other taxa in the family in the high mountains of New Zealand. I read about the geography of this widespread family and decided that I would study the evolution in this family using immunology of plant proteins. My approach was pretty crude, even by the standards at that time, but I worked entirely on my own (well, I got some help in injecting and bleeding rabbits!), conducted experiments and wrote up a report. I was given a key to the science building, so that I could use the equipment at any time of the day. In doing this research, I learned that it was conducted in a few other places, mainly in Europe, but notably in the laboratory of Prof. David Fairbrothers at Rutgers University, in New Jersey. I wrote to him, describing what I had been doing and asking some questions about methods. He quickly replied, answering the questions and suggesting that I look into the possibility of continuing this research as a graduate assistant in his laboratory.

GRADUATE STUDIES AT RUTGERS UNIVERSITY

In January of 1966, David Fairbrothers met me at the plane in a driving snow storm in Newark, and took me home to spend my first days with him. Then I quickly settled in graduate student housing and started my graduate studies as his student. I was a teaching assistant in biology during my first semester, but was supported as a research assistant for most of my five years at Rutgers. I began to continue research on the seed proteins of members of the Ericaceae, but found it impossible to extract proteins from their tiny seeds, and I abandoned that project after eight months of hard work. I took advanced courses in immunology and biochemistry, plus plant systematics from David Fairbrothers. I became friends with several very human and supportive professors, whether I had a course from them or not. Jim Gunckel instructed me in anatomy and microtechnique. Carl Price instructed in Physiology and Plant Biochemistry, Barbara Palser (who was a member of my graduate committee) in plant morphology and embryology, Charlotte Avers in cytogenetics and Ovid Shifriss (also a committee member) in the evolution of domesticated plants. I liked all of these courses, particularly because the instructors were active in research and expressed their enthusiasm in the material. I didn’t take courses in ecology, but was surrounded by a very strong graduate ecology program. I knew Murray Buell, Jim Quinn, Paul Pearson, and hung out with a number of ecology graduate students. I attended the excellent ecology seminar series every week, and learned quite a bit about ecology through this exposure. Richard Forman, today acclaimed for his work in establishing landscape ecology as a legitimate field of study, arrived my second year of studies. I took bryology and lichenology from him, which involved a long field trip to West Virginia, and I helped with some of his field research on Mount Washington, in New Hampshire. A decade later we renewed our friendship when we both pursued our research interests in Montpellier, France.

The Fairbrothers lab group taking a roadside rest during a field trip in upstate New York, 1968. From the left: David Fairbrothers, Jerry Pickering, Gary Hildebrand, Roy Clarkson (a professor on sabbatical leave from the University of West Virginia), Steve Osborne (sitting), and Art Tucker.

Although the coursework was useful, I learned most from talking (and arguing) with my fellow graduate students, quite a diverse crew. Some new friends from my graduate immunology course took me under their wings to teach me something about urban life, classical music, and Jewish culture (of which I was totally ignorant). Much of our conversations were in labs and corridors rather late at night, In Nelson Laboratories. I met and became friends with Rod Sharp at this time. I also became friends with the Lutheran Chaplain and his wife, Warren and Joan Strickler, organizing a tutoring program for disadvantaged kids and attending organ and choral concerts of sacred music. It was a very interesting and stimulating period for me as a graduate student. Although my research involved local collecting and lots of laboratory work, I was able to take some time to travel to the tropics (Puerto Rico and Venezuela) and walked in tropical rainforests. These experiments helped sustain my interest in studying plants, counterbalancing the grind of long hours of laboratory research. My period of graduate studies was a time of great social upheaval in the United States, catalyzed by protests over the war in Indochina and civil rights issues in the U.S. Race issues had not been important to me while growing up, because I hardly knew any black students, other than a couple of athletes from the nearby town of Moses Lake during my high school years.

My graduate study years were important in my emotional maturation, and also in developing some social confidence in meeting and working with a variety of people, from diverse cultural backgrounds. I became aware of the gay and lesbian community, and my tolerance of different people and lifestyles was greatly expanded. I was active in the Graduate Student Association, playing in their basketball league, attending the weekly receptions (free beer) and editing the Graduate Student Guide.

I switched my research from the phylogeny of the Ericaceae to a masters project on hybridization and introgression in cat-tails (Typha), which expanded more broadly in the monocots, and to the study of the inheritance of isoenzymes for my Ph.D. In addition to the immunological techniques, I acquired other techniques of protein identification and purification, particularly polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE as we now know it) and isoelectric focusing. I expanded my research to include the inheritance of seed proteins in castor beans, using varieties provided by Prof. Shifriss. The use of electrophoresis and the study of multiple forms of enzymes were very recent developments in biology, and our lab was on the forefront of this research. My dissertation committee consisted of David Fairbrothers, Barbara Palser, Oved Shifriss, and Nicolas Palczyuk (an immunologist).

My advisor, David Fairbrothers, was an excellent mentor. He was an accomplished scientist, a leader in the University, and led an active research program with several graduate students, undergraduates, and occasionally a senior faculty member visiting on sabbatical leave. Despite his busy schedule, he met regularly with us, and was available for personal advice when it was really needed. When I was finishing my dissertation, the University shut down over protests against the invasion of Cambodia. There was such turmoil that the completion of my Ph.D. seemed meaningless. When I talked to David about this he related to me an event in an all-university faculty meeting just held about the shutdown. A young faculty member stood up and declared to all present that he was fed up with the attitude of the administration and the stance of the University, and declared that he was resigning. Another even younger faculty member near him also declared that he, too, would resign. Later on, David learned that the first speaker had been denied tenure and was leaving anyway, but not the second speaker! The story was shared to encourage me to keep a balance and a vision for the longer run about things. He had suffered grave danger and privation during his service in Europe during World War II, particularly during the Battle of the Bulge. He didn’t share any battle stories with us, and I only began hearing about his experiences during the last eight years, but those experiences gave him perspective and patience.

I received my Ph.D. in June of 1970, with my parents in attendance. I continued research that summer and then drove my old black ’57 Chevy station wagon full of all of my possessions (mostly books and records) to Columbus, Ohio, to begin a post-doctoral fellowship at The Ohio State University.

OHIO STATE

I had received an offer of an Ohio State University Post-doctoral Fellowship, to work under the supervision of Don Dougall, who was an Associate Dean in the newly formed College of Biological Sciences. Within days of my arrival I helped the lab move into a brand new life sciences building, devoted to research in cell biology and microbiology. My academic home was actually the Department of Microbiology. Don did research in plant tissue culture, looking at the biochemical clues to cell and tissue differentiation in the wild carrot system. He wanted someone with some background in protein chemistry to help him identify enzymes, particularly glutamine synthetase (which he believed existed in two different forms that responded to the growth regulator treatment that led to the formation of embryos). Rod Sharp had mentioned me, and my training (my “tool kit”), and he was instrumental in my selection.

Rod Sharp, taken during a free-wheeling night discussion at Nelson Labs, Rutgers University, around 1967.

In biological research there has always been a little tension between “questions”—and hypothesis testing—and “techniques” (the tool kit part). The danger of focusing on the techniques was that I’d lose touch with the scientific reasons for conducting the research, and I was, at that time, a little critical of focusing on techniques. Yet, I was the beneficiary of practical learning of all sorts that boosted my scientific research, including carpentry and metal work. I didn’t think about it too much at the time, but it was clear that the techniques I’d mastered gave me the post-doctoral opportunity I accepted, and not any basic research results I’d achieved.

My fellowship lasted one year, and Don moved on as Director of the Alton Jones Cell Science Center in Lake Placid, New York. I continued doing research a second year, and obtained support from various academic units, even the Institute of Polar Studies. I did research on the wild carrot system, looking at differences in isoenzymes, and helping Don with his glutamine synthetase research, but I did not enjoy the research and found the long hours in a windowless building to be oppressive. I could not envision myself spending the rest of my life doing such work. I did get involved in many side projects that were rewarding, such as creating multi-media programs for teaching basic biology, and I had a wide circle of friends. One of my childhood friends, Larry Reeker (the artificial intelligence guy) was a faculty member in the Computer Science Department. Through Larry, I made friends with several grad students and young faculty members. Tom Defanti, who later became an acknowledged expert for his work on internet-2 and virtual reality environments, shared an apartment during my second year. Also, my time in Ohio helped me do some additional research beyond my dissertation, and provided the time to write manuscripts that led to the three articles that originated from my Ph.D. research.

The most important event during my stay at Ohio State was meeting and ultimately marrying Carol Rotsinger. Carol was an art student, recently returned from a long trip to Europe and Asia and finishing her degree in Art Education. We met through mutual acquaintances in the Computer Science Department. We met and talked one evening in late March of 1972 at Bob Jones’ house, and that brought us together; we married the following August in a remnant hardwood forest, The Gahanna Woods, on the edge of Columbus. I write this chapter after four decades of marriage.

From the beginning, Carol and I shared a formless spiritual yearning, not Christian or denominational in any sense. For Carol it was supported by her experiences from travelling in the east, for me by my experiences in nature. We became interested in the teachings of G.I. Gurdjieff, who had come to the west to help people have an experience of their Self. We heard about these teachings from two childhood friends, Allan Lindh and Curtis Amo. We began a correspondence with a leader based in Warwick, NY, where Curtis and his wife Laile had moved to participate in an intentional community, The Chardavogne Barn, under the leadership of Dr. Willem Nyland, a student of Gurdjieff’s.

THE UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA

As a graduate student, I had corresponded with Benjamin Stone who was an American plant systematist working at the University of Malaya, in Kuala Lumpur. Ben was quite a remarkable man and was the world’s expert on the classification and evolution of the Pandanaceae, a family of ecological and economic importance in Asia. I had needed seeds of members of this family for my immunological work, and he had helped me. He had also wondered if I might be interested in a faculty position in experimental taxonomy at the University of Malaya. This idea stayed with me and I begin to pursue this possibility as a post-doc. In 1972 I received an offer of a lectureship and tentatively accepted it. There was a long process of visa application that took time, and I was anxious about the reality of this actually happening as the wait stretched into months. I was attracted by the possibility of studying plants in the rainforests of tropical Asia, and also by the cultural and spiritual traditions of the east. The position at the University of Malaya was not only a work opportunity for me, but also a life for a newly married couple. We arrived in Kuala Lumpur in February of 1973.

My Malaysian mentors on the Genting Ridge, in the mountains outside of Kuala Lumpur, 1973. We were looking for specimens of the rare and newly discovered Malaysian citrus, Citrus halimii. Left to right: Peter Ashton, Benjamin Stone, and Brian Lowry. Our dog Pooch (whom we received from Brian) is in front.

When I went to the campus to begin my work I found a mixed faculty of European/ American expatriates, along with the Chinese, Malay and Indian Malaysian faculty. The Chinese were shocked and a little dismayed to see me, David Lee, of European descent; they were certain that a Lee would be Chinese-American. The Malays were quite pleased. It was a good faculty, the students were bright and hard-working and, at that time, represented the cultural diversity of the country. My teaching load was quite modest; I had a nice laboratory, and a young Chinese-Malaysian woman assigned to me as a laboratory assistant. We lived in university-subsidized housing a short distance from campus. My knowledge of the natural history of Malaysia was primarily derived from reading Alfred Russel Wallace’s The Malay Archipelago, but I learned quickly from my colleagues and frequent field trips.

It was an interesting time in Malaysia. It was a new country, having split from Singapore a few years earlier. There were also racial tensions, primarily between Chinese and Malays, that had led to riots four years earlier. In the aftermath, there were sincere efforts of reaching out, particularly manifested during the cultural celebrations of the separate communities. We saw the seeds of Islamic fundamentalism taking root, particularly in the more rural east coast states, but the Islam of Malaysia in the 1970s was tolerant. There was a strong British influence in local institutions, befitting its colonial past. I understood the phrase “red-tape” (bureaucratic inefficiency) when I visited government offices and saw the shelves over-loaded with bundles paper…..all bound in pink or red fabric tape. I joined the Hash-House Harriers, an old running association. We met at regular intervals to follow a paper trace (with numerous false leads, and there’s another phrase rooted in British tradition) through secondary forest, oil and rubber plantations, and scrub (belukar) eventually returning to our starting point, where a truck full of iced beer was awaiting. We inherited a dog, Pooch, who was an institution on the “Hash.” Pooch was with us until shortly before we left Malaysia.

The shock of being in such a new place, foreign and yet quite westernized, far from family and friends, was hard on our new marriage, but we weathered the storm and had a really wonderful four years in Malaysia, with occasional trips to India, Indonesia (Java, Bali and Sumatra) and Thailand. Carol found enjoyable work in teaching printmaking to fine arts students at the Mara Institute of Technology (the MIT of Malaysia!). My mentors in learning about the biodiversity in Malaysian rainforests were Benjamin Stone (for plant diversity), Brian Lowry (phytochemical diversity) and Peter Ashton (of the University of Aberdeen and a frequent visitor, plant diversity and ecology). With frequent trips to rainforests in the mountains east of KL, I gradually became more familiar with the diversity and more comfortable in exploring the forests. Each year, faculty and the 20 or so B.S. Honors students would organize a research trip to a rainforest area to teach learn botany and ecology, and collect plants. These were also a valuable mechanism for me to learn about plants and natural history, by listening carefully to my colleague’s discussions with students, as Engkik Soepadmo on plant diversity and Ratnasabapathy (“Ratna”) on limnology.

Although I had been selected for the post because of my research expertise in cutting-edge techniques to address plant systematic problems, I became more and more interested in the general phenomena that I saw in the forest: (1) the physiognomy of understory plants adapted to very low light conditions; (2) the presence of iridescent blue plants in the understory; (3) the production of brilliant red young leaves; (4) the frequent presence of red undersurfaces of understory plants, (5) the presence of lectins in seeds of legumes, and much more. Gradually my interests turned from systematic botany (although I published a couple of systematic papers from work there) and moved in the direction of plant functional ecology. That meant learning more ecology (my experience at Rutgers among ecologists gave me a good start), and learning new techniques. Basically, my experiences in Malaysian rainforests gave me the research questions that I pursued for the rest of my scientific career.

David Fairbrothers and myself, showing off our new hand-printed batik shirts at the banquet for the inauguration of Rimba Ilmu, in 1974.

After a year of living in KL, Carol and I decided to move to a rural valley south of the city, Ulu Langat. A couple of faculty friends lived there, and we learned about an empty schoolmaster’s house (the “rumah guru besar”) in Kampong Sungei Serai (the village of the lemon grass stream). I pursued its rental within the bureaucracy of the Ministry of Education and eventually persuaded them to rent the small house to us. We occupied it for about 6 months before the electricity was turned on. It was a great move. There was secondary rainforest behind our house and the protected forest of a drinking water catchment within walking distance. At the head of the valley there was an old British hydroelectric project that provided walking trails up to the points of water intake and into the hill forests and the highest mountain, Gunong Nuang, with moss forest at its summit. Near the head of the valley there were a couple of villages of orang asli, or aboriginal people. These were the Temoin, and they became important sources of information, as well as guides for more extensive trips into the forest. I set a goal of learning all of the walks to places of scenic beauty and of natural historic value in the valley, and our dog Pooch was an invaluable companion on those trips.

Carol and myself on the steps of our home at Kampong Sungai Serai, in Ulu Langat, M alaysia, in 1975. Pooch is with us.

We became involved in various affairs in KL and the university. Carol’s work in the arts led to contacts with local artists. I became a board member of the Malayan Nature Society, which is now the Malaysian Nature Society and the most important nature conservation and education organization in the country. I went on, and eventually led, nature walks in different areas near the city. Ben, who became a great friend and mentor, was in the process of establishing a new botanical garden, Rimba Ilmu, on the edge of the University of Malaya campus. I helped, particularly with the symposium held at its dedication. I was able to invite David and Marge Fairbrothers, and David gave a plenary address at the symposium; they had a wonderful visit.

At the beginning of my stay, I enrolled in an intensive Malay course offered by the same instructors who trained Peace Corps volunteers. There was a large contingent of volunteers, several became friends. Jack Putz, now a Professor at the University of Florida, was a volunteer working at the Forest Research Institute, and became a friend. My skill in Malay was adequate for me to travel comfortably in rural areas throughout Malaysia and Indonesia (it had been the market language for the region) to meet and greet local people and ask them about the plants they collected and used. We also learned phrases in Mandarin (spoken by the educated Malaysian Chinese) and Tamil (most of the local Indian residents had originated from South India); this helped us to function socially, although the students and educated older population spoke excellent British style English.

During our sojourn in Malaysia, the magnitude of the pressures of development and the environmental problems became clear to me, and my personal response was to help develop programs in environmental education. I wrote the first book on environmental problems in the region, The Sinking Ark (published by Heineman Books in 1980), and I wrote articles for general publications, as business magazines, etc. University-bound Malaysian students sat for a British style comprehensive exam, the scores for which determined whether they could gain entrance into a local university. Traditionally, the exam had included questions and tested on materials more appropriate for a British student than a Malaysian one (the exam was for the Cambridge Higher School Certificate). My colleague and neighbor, Norman Williams, and I wrote the first biology exam review to fully use Malaysian examples and thereby influenced the direction of curriculum development. I also received a grant from the Ford Foundation to produce filmstrips and slide sets on various topics to put more local examples in the science curriculum. On days away from the university in Ulu Langat, I began to explore the valley for specially attractive village settings (and the villages were settled by Malays from different parts of Indonesia, with different cuisines and arthitectures), attractive forest and streams, waterfalls, and routes towards Gunong Nuang. I had made contact with R.E. Holttum, a great British botanist who had worked in Malaysia, and I collected thelypterid ferns from various locations for which he was producing a taxonomic monograph. The results of my travels in the valley was the production of the first hiking guide written in Malaysia, and published in the Malaysian Naturalist in 1976: Trips and Tracks in Ulu Langat.

There was a rhythm of life in Malaysia that was initially frustrating to us, but eventually was very attractive. Things needed for research arrived with much delay, just like the visas that had frustrated our arrival. However, once those obstacles were accepted I was quite amazed by my productivity in completing projects and publishing research. My first letter in Nature was published in 1975 from research on an iridescent plant (and a second Nature letter was co-authored in 1977). We were blessed with some good friends, and I remain grateful for the friendship and knowledge of Ben Stone. Carol and I were also fascinated by the different sacred traditions in Malaysia, especially the Hindu and Buddhist ceremonies and the Sufi teachers, and they reinforced the sacredness of the nature I was privileged to study.

Ben Stone and David Fairbrothers shared a trait that eventually influenced me. I never heard either Ben or David speak badly of another person, no bad-mouthing or speaking behind the back. If they thought ill of someone, they remained silent. That silence, then, would speak volumes.

A number of eminent scientists visited us in Ulu Langat. Paul Richards, the author of the iconic Tropical Rain forest, was one. I had read this classic as a college student, and actually went up to Seattle to hear him lecture at the Forestry School of the University of Washington. I was gratified to see my work on understory plants covered and cited in his 2nd edition of 1996. Egbert Leigh also visited, as did Max von Balgooy, the Dutch plant anatomist. Francis Hallé, known for his work on tree architecture and the canopy research platform, Le Radeau des Cimes, stayed with us in Ulu Langat, and we became good friends.

My initial contract was for three years, and I asked for, and received, a one year extension. One important purpose of the expatriate faculty was to identify talented local students, train them, and help them obtain graduate training overseas—all so they could return and take over our jobs. In my last visit to Malaysia in 2005, to study the physiological function of blue iridescence in understory plants, I visited my old university (now the Universiti Malaya) to meet an old student as the Dean of the Faculty of Science, and another as the Chair of the Institute of Biological Sciences. Former graduate students whom I knew had senior research positions at the Forest Research Institute of Malaysia, where I later did research on shade responses of tree seedlings with NSF support.

Thus, we made plans to leave at the beginning of September of 1976, and began a long odyssey back to the United States.

All told, I have lived and worked in tropical environments for some seven years, including living in Malaysia, the dozen or so 1-2 month trips for research throughout the tropics, along with two years of living in India. Our return to the U.S. took about eight months, all of this travel by someone who had lived in an isolated and rural town in eastern Washington State, and did not leave the northwest until that trip to the South Pacific at the age of 21 years. Well, that first trip certainly was a stimulus, and as a child I read voraciously about other parts of the world, devouring every issue of National Geographic. I also collected stamps, and enjoyed learning about the countries from where the stamps came, so that I could understand the importance of the images on the stamps. I mention this here, because the experiences were an inspiration for later research and writing. An important part of these travels has been meeting with scientists and visiting educational institutions, almost always giving seminars. I also became interested in the use of plants by local people, always visiting farms and local markets and learning of various products raised and collected by them. These observations (including color transparency photographs) were important for later teaching in introductory and economic botany, as well as tropical botany and ecology.

On our return voyage, we spent ten weeks in India, starting in the south and residing in the high foothills of the Himalayas, in Himachel Pradesh, for one month. We also spent some time in Delhi and in Rajasthan. We left India in early December on a Syrian Arab Airlines flight to Damascus (the cheapest ticket) and spent 10 days in Syria, before flying on to Greece. We expected to spend some time in Athens and then move along the southern coast of Europe. However, we did not anticipate the winter coldness in the Mediterranean region, so we decided to stay some time on Crete, in the middle of the Mediterranean—but it was quite chilly there, as well. From Crete we flew back to Athens, and then decided to travel across North Africa. We flew to Cairo and visited for a week before travelling south to Luxor, and then on to Aswan. We visited this venerable city during the street riots of 1977, the last to precede the revolution of 2011. We travelled south to avoid the winter temperatures, and Luxor was about right in January, with warm days to ride bikes to the Valley of Kings, and chilly evenings with star-filled skies. We travelled across North Africa through Tunisia and Algeria, with a longer stay in Fez, Morocco. We then ferried across the Straits of Gibralter to Spain, then France and Switzerland, to England, and then home on April 20, 1977. While in France, we visited Francis Hallé, and in the United Kingdom I visited Eric Holltum at Kew and gave a seminar there, and we travelled north to stay with Peter and Mary Ashton in Aberdeen.

We found the U.S. a different country from the one we left, more at peace and more tolerant. We had decided to accept an invitation by Francis Hallé to work and teach in his Tropical Botany Laboratory at the University of Montpellier II. In the interim, I practiced my high school and college French, and we travelled around the country for almost five months. We did this with care, as Carol was pregnant with our son Sylvan, but we had been gone well over four years and had family, relatives and friends with whom to renew ties. We also visited some local groups involved in Gurdjieff work as we continued those studies.

THE UNIVERSITY OF MONTPELLIER

I had been appointed a Maître de Conférènce Associé (Visiting Professor) at the Institute Botanique, Université Montpellier II, for a year with a possible extension for a second year. My duties would be to assist Francis with the running of a post-graduate diploma program in tropical botany that attracted students from all over the world. This meant giving lectures in tropical botany, including illustrated talks on tropical plant families. We arrived in Montpellier on 24 September. Carol was now over 7 months pregnant, but our settling in was smoothed by the support of Francis and Odile Hallé and their four interesting and loving children. With their help, we bought an old Simca automobile (a baignoule!) and rented an apartment at the Chateau de la Mogère, just to the south of the city. It was a beautiful 18th century country estate (** in the Michelin Guide), once owned by the great French paleobotanist Gaston Saporta in the 19th century and with a formal garden. We actually lived in one of the outbuildings of the farm, a massive two story structure with ~2’ thick stone walls (which made the place super cold during the winter). Francis quickly learned how bad my French was, so we both enrolled in intensive courses, Carol for survival and me to support more professional lecturing and interactions. I’m reminded of the extent of my learning from a visit to the rustic countryside outside of Montpellier where a local farmer asked if I were from Belgium; I later learned that the French found Belgian French to be crude and unacceptable! After I finished the French course, Francis told me that I could teach graduate and senior undergraduate students, but that the first and second year students would laugh at me. So, I limited myself to that group of students.

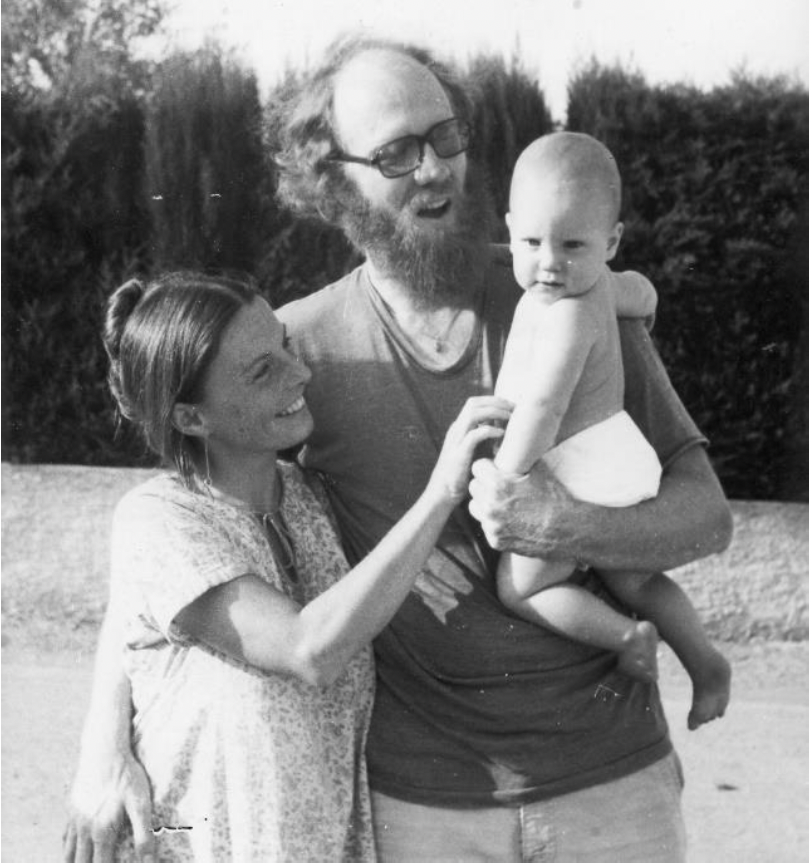

Carol and I with our newly born son Sylvan, at the Mogère near Montpellier, spring of 1978.

My old friends Richard and Barbara Forman from Rutgers days took their children to Montpellier for a year where Richard worked with Michel Godron of the CNRS Ecology Laboratory to write the first book on landscape ecology, thereby establishing a new field of investigation in ecology. They were particularly supportive after the birth of Sylvan on November 9th, as were Francis and Odile.

In late January 1977 Francis and I flew with the diploma students, and some other scientists, including Patrick Blanc, to Cayenne, French Guyana, for a month of tropical rainforest field research. During that time, we stayed at locations adjacent to, or within, tropical rainforest. A highlight was a flight to Saȕl, where we made a three day trip to Mt. Galbao, high enough to support montane forest. This was my first experience of forest of the Amazon region, and having Francis and other botanists well-acquainted with the vegetation enabled me to learn a lot of botany and take lots of photographs. I was also able to make observations on the physiognomy of plants, compared to my experience in Southeast Asia.

After our return from French Guyana, I was busy lecturing and helping students work on their short graduate theses. I became quite interested in the history of science, botany in particular, in this old university city. French professors took 2-3 hour afternoon breaks for lunch and a snooze. Since I usually rode a bike from La Mogère to the University, it was inconvenient for me to commute during lunch. So I’d have a quick lunch with the diploma students, and then explored the city and libraries for a couple of hours, looking for documentation of the importance of Montpellier (as locating the old homes—“hotels”—of Pierre Magnol, and other luminaries) and visiting libraries, particularly that of the University Medical School. Since the science of botany rose out of medicine in 15th century Europe, the Medical School library, adjacent to the institute and botanical garden, and near the cathedral, was a rich source of old botanical books and illuminated manuscripts. Montpellier had been an important center for the study of medicine and natural philosophy since the 12th century. Many great figures in botanical history (the Bauhin brothers, Clusius, Magnol, Rondelet, and others) had studied there as medical students. I photographed hundreds of illustrations from old botanical works and learned about them. At that time, I could request an old illuminated parchment manuscript of Hippocrates or Galen, have it brought to me, and could photograph it as I wished. I photographed hundreds of illustrations from these works and learned about them. This documentation assisted me in injecting history into my lectures on botany and biology in the next 30 years of university teaching.

I didn’t do very much research in Montpellier. I did establish a collaboration with Charles Hébant for electron microscopic research, which we published in 1984, and wrote several manuscripts from late Malaysian research that were published in 1980 and after. However, it was a stimulating year for thinking and talking about tropical botany, with Francis, and many eminent figures in tropical botany. I first met Barry Tomlinson in Francis’ lab, and proof-read the galleys for Tropical Trees and Forests. An Architectural Analysis, one of the seminal works in tropical botany in the past half-century.

By early June, the university term ended, and students and faculty dispersed. Francis and family went to their summer cottage on the Ǐle de Groix, off the coast of Brittany. We visited them for a time, but mainly relaxed in Montpellier, staying in their vacant home. I made many bicycle trips to small villages with old Roman monuments and Romanesque churches. After a brief rest on the Mediterranean coast, we returned to The United States 22 September, 1978.

WARWICK, NEW YORK

We moved to Warwick, New York, to join the Chardavogne Barn community to more intensively involve ourselves with the Work, as outlined by G.I. Gurdjieff. We had corresponded with a member of the community and had read extensively, and I had also written my old friend Curtis Amo. Curtis and Laile were there for us when we arrived, and we rented the house they left to move into another home they had purchased. Activities at the Barn included group meetings, service/work days, and movement classes. There were special days, as Gurdjieff’s birthday, when many students came from New York City to the “wilds” of upstate Orange County, Warwick was a township, and included a fair amount of countryside (fields and forests) as well as several villages. We lived in an early 19th century farmhouse in the village of Amity. Shortly after our arrival, Carol became pregnant, and our daughter Katherine was born in July of 1979.

There was the question of making a living in this new place, and we were naively optimistic. I had decided to write articles for magazines and produce educational materials as a major supplement to our income. I also prepared a proposal for a trade book about tropical plants, and met some editors in New York City. There was some interest by Viking Press, but their market analysis discouraged any further discussion. Thus, I pursued a number of jobs, involving skilled manual labor, to make a living. Members of the “Barn” ran businesses (often cooperatively and with the intention of making that labor an extension of the Work). In Warwick Village there was a bookstore, craft gallery, and auto repair shop, all run by members of the Barn. The people at the Barn came from very diverse backgrounds, but generally were highly educated and with interests in the creative arts; we made several friendships. We helped in the community day care program, and I was a volunteer teacher in the community school, which taught children from kindergarten to grade six. So, I performed the following work: landscaping, carpentry and home building (my principal occupation), apple picking, and piano re-building and regulation. I looked around for some part-time teaching. I was hired to teach biology to nurses at Orange County Community College in Middletown for a semester. Then I was hired to teach general biology and environmental science courses at a new private community college campus run by Upsala College, in Sussex, New Jersey. Upsala was a Lutheran liberal arts college, much like Pacific Lutheran where I had studied as an undergraduate, and this new campus was hoped to breathe some life into a college that was shut down a few years later. Also, through the support of Iaian Prance, who was then the Vice-President for Research at the New York botanical Garden, I became an Honorary Research Associate, to help me keep my academic life alive.

We continued the spiritual work at the Barn, but it was clear that no one was truly knowledgeable of the teachings of Gurdjieff, as his student and the founder of the Barn, Dr. Nyland, had passed away two years earlier. On the 26th of August, 1979, just a few weeks after the birth of our daughter, the Lee family drove an hour north to South Fallsburg, on the edge of the Catskills, to meet the Indian meditation teacher, Swami Muktananda. We had seen posters about his visit in Warwick. My first meeting with Baba, as we called him, changed my life. I began to meditate regularly, and had deep experiences of the truth that exists within each of us. It was revolutionary. Other members of the Barn were also visiting the Sri Muktananda Ashram, and having similar experiences. Eventually, we gradually pulled away from many of the activities of the Barn, and took on the discipline of meditation and the ancillary activities of chanting (to still the mind) and the study of various teachings in the Hindu spiritual tradition, such as the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita.

At about the same time we first encountered Baba Muktananda, Barry Tomlinson, an eminent Harvard Professor of tropical botany (who was a friend of Francis and a co-author of the book Tropical Trees and Forests: An Architectural Analysis and who I had met in Montpellier), told me about a job at a new university in Miami: Florida International University. These were the days before the internet, and it was difficult for me to learn about this place, other than it was a state university which had begun to instruct students in 1972. At any rate, with little expectation (and I had been applying to other schools, with little interest—mostly no response at all), I sent in an application. Sometime later, I received a response and, eventually, an invitation to come for an interview. Then I was offered a position. We accepted. I needed a job badly to properly support my family, and it seemed that I would be able to pursue the research interests that had been ignited in Malaysia in this strange place on the edge of the tropics. Thus, we continued our life in Warwick, with friends from the Barn, teaching, building houses, and visiting the Ashram—until it was time to move.

It is useful to review what I had learned in that I would take with me to this new life and professional position in Miami, at the age of thirty-eight years. I had developed a “spiritual” curiosity and yearning, deeply informed by experiences in nature and in eastern philosophy. I had accumulated a strong classical background in botany with familiarity of the physiology and biochemistry of plants (at FIU I would teach Plant Physiology and Tropical Botany, and help out in General Biology). I had a rich practical experience of the tropics, particularly the Asian tropics but with some field work in the new world tropics, as well. I had learned much by observing traditional cultures and their uses of plants (I would later use this in the courses of Introductory Botany and Economic Botany). I had moved my research from experimental systematics into functional ecology, although I still had much to learn about new techniques being developed to study the function of plants. I had also matured as a person, and that was a slow process. Coming from a good family, with the support of my parents, made a good start. I had learned about persistence and hard work through sports, and was fortunate to have some really good teachers in high school. I was aided by the support of mentors, as David Fairbrothers and other Rutgers faculty, by Benjamin Stone and Francis Halle. Mostly, I learned through my marriage to Carol and acknowledging the responsibility I had for nurturing the development of our two children. Although I had accepted the offer of a position at the Assistant Professor level, my experience was far beyond that.

I had been a member of one professional society throughout that time, and even today: the Botanical Society of America. David Fairbrothers strongly recommended such a commitment, and I joined in 1966—now 47 years! I also learned an invaluable lesson from an old neighbor and family friend, Paul Hamilton, from a hospital bed as he was dying of cancer. Paul had risen from running a hamburger restaurant in my home town of Ephrata to become the Secretary of the Department of Ecology for the State of Washington. He shared with me the secret of his success: work hard to make the institution a more effective and successful, but never take credit for any of the fruits of your labors—leaving that to your superiors, as they will take care of you, encourage and support you in your career.

MIAMI AND FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY

We arrived, moved into a temporary home, and I arrived for work at a new university. I found Florida International University (FIU) a new, highly immature in good and bad ways, and very idealistic place. It had opened eight years previously with about 6000 students, the largest initial enrollment of any university in U.S. history, and was at about 11,000 students in 1980. The statistics were a bit misleading, because the number was a head count, and did not reveal that 80 % of the students were older and with jobs, and part-time enrollment. They were a lot of fun to teach; they were mostly older (mean student age of ~28) and serious about their studies. FIU was in the process of becoming a more main-stream university, with a four-year program (in 1980 it was taking community college transfers and had a few graduate programs in education and business) and a breadth of graduate programs. It had two campuses. The south, and principal, campus where I taught was on the site of an old municipal airport, and a smaller campus was located in the northeastern corner of the county, on Biscayne Bay—the site of a botched trade exposition. As a young university, there was an urgent need for faculty involvement in institution building. It was important for the university, students, and the ultimate success of faculty and faculty scholarship. There was also a need for institutional involvement in the community. Despite its glitz, Miami has always been a poor city, seen in low family income and the percentage of school-age children eligible for free meals. FIU as a public low-cost university was a needed addition, to the few private institutions, particularly the University of Miami.

The Department of Biological Sciences had an interesting mix of faculty members. Many had unusual records, with international experience similar to my own, and were mostly relatively early in their careers. However, not much research was happening, and there were no real opportunities for graduate study. The department was located in an interesting setting, on the edge of a very cosmopolitan and Latin city and surrounded by tropical marine and terrestrial ecosystems. So, the opportunities to study tropical plants were excellent. Furthermore, Miami was well-connected to countries throughout the neotropics, and there were lots of opportunities for research there, supported by the university’s strongest academic program, The Latin and Caribbean Center (LACC).

In Miami, I renewed my friendship with Rod Sharp. He arranged my giving an invited talk at a national food science meeting (on exotic tropical fruits and vegetables), and enlisted me as a horticultural consultant in providing plant materials for the newly formed DNA Plant Technology, Inc. (DNAP).

My efforts at FIU were well divided into teaching, service, and scholarship. In retrospect, I believe that my most inspiring college and graduate school mentors led the way in showing that it wasn’t just about research (and certainly the most efficient way to success and salary increases was to minimize teaching and service and focus on the success of research—visibility and outside funding). The two individuals who were the most influential were Jens Knudsen at PLU and David Fairbrothers at Rutgers. In my previous academic position at the University of Malaya, I had little impact on the institution, partly because I was an expat; my efforts went into research and teaching.

Teaching. I was hired to teach two courses that had been regularly taught by my single predecessor and were part of the regular curriculum: plant physiology and tropical botany. Plant Physiology was taught with laboratory, and most of the biology majors took it. It fulfilled the graduation requirement for (1) a plant course; (2) a physiology course; and (3) a lab. I quickly developed the reputation of being organized, fair and interesting (I was able to integrate my extensive experience into the course). This was also true for Tropical Botany, a course taken as an elective by biology majors and Environmental Studies majors. That course included lecture and laboratory, and the latter was primarily visiting local plant communities and learning about plants: their functional ecology, development, systematic relationships, and uses. In 1988, we hired a plant physiologist, Steve Oberbauer, and I stopped teaching that course. I had taught other courses, as plant morphology and economic botany, to later drop them as we hired faculty in those specialties. I taught a portion of the general biology course, for a special program for gifted high school students. In 1984, FIU was granted the ability to establish four year programs, and I began to teach in the general biology course for our own freshmen students. As the lower division program expanded, a need to add our offerings in first year non-major science courses was partly fulfilled by my offering of a non-major introductory botany course. I developed a style of teaching that was most effective for upper division students, but over time (particularly in the last 10 years of my work) I became more frustrated by my ability to reach the first-year general biology students; as the university grew, those students became more traditional, i.e. 18-19 years in age, fewer with jobs and supported by their parents. Our teaching loads were somewhat intermediate between a teaching college and a high level research university. It was more of a challenge to do research, but definitely doable.

The aftermath of hurricane Andrew in 1992 was a traumatic time for Miami and our family. Our home was seriously damaged during the storm, and it took four months of repairs before we could move back into our home. I was particularly struck by the damage to our urban landscapes and how emotionally affected we were by it. It was difficult to drive around with familiar tree landmarks lost. I contemplated the impact of these changes and came up with an idea for a totally new and inter-disciplinary course: “The Meaning of the Garden”. The course was offered by the Liberal Studies Program, and I received students with all sorts of interests. The course met once a week, on Friday, and began with about two hours of physical work on various garden projects, including weeding and planting. The students then washed up, had a cold drink, and we re-assembled for a lecture/discussion section. The topics often were delivered by outside experts in landscape architecture, ethnobotany, horticultural therapy, art history, poetry, and more. I found that the physical work by the students together created friendships and broke down barriers that inhibited free discussion. I assigned writing projects, including an autobiographical essay on “my first garden experience” and a Haiku. The greatest student effort went into a project, and I worked with each student on defining what that project would be and how the student was connected to it. At our final class meeting, we created a reception like environment with excellent snacks (some of which were products of their projects) and the students gave presentations on their projects to everyone present. This is the only course I’d taught where several students told me that it had changed their lives. However, even today I occasionally run into former students who mentioned that my lectures on plants had made them interested in the environment or in gardening. In our non-major botany course, each laboratory section produced and maintained a garden plot on campus, and students could consume its products at the end of the spring term (gardening is a winter activity in Miami).

I reached out beyond the university by giving talks and making friends with groups interested in plants. I made a particular effort to connect to the large nursery and landscape nursery, mainly centered in the Redlands, an agricultural area south of Miami. I gave talks at their meetings and was able to obtain a book fund from them that added plant titles to our library collections. Early in my teaching career, I was involved in the training of science teachers in botany (many of them had learned human physiology and kinesiology, and were coaches) during the summer. This also helped to enhance my nine month salary a bit. I also took up carpentry jobs during summers for several years.

Service. On one hand, tenure-earning faculty members like me were not encouraged to take on too much service, but circumstances in the department demanded it. My first service assignment was as head of the Curriculum Committee. In that I also was a member of the College Committee. It was interesting to me to see how new courses were developed and approved, and then became part of the course descriptions of the State University System, and assigned a course number. Issues came up for courses of an interdisciplinary nature that required consultation with cognate departments. In time, I also served as member of the Faculty Senate.

When I arrived at FIU, there was no advanced degree program in the department. The amount of research improved steadily after my arrival (not just because of me, as a majority of the faculty was motivated to pursue research). We could produce M.S. students through a master’s program run by the School of Technology, in “Environmental and Urban Systems”. Then, we established a cooperative program with Florida Atlantic University. This was a sister member of the State University System, slightly older than us, and some 60 miles north, in Boca Raton. They had an M.S. program and allowed us to produce master’s theses through them. This was onerous; theses were defended in Boca Raton, and also demeaning because our faculty was more energetic and research-minded than theirs. I became chair of our small graduate committee, and created and guided our proposal for an M.S. degree through the university. By 1984 we had received approval for our own independent M.S. degree. We had serious problems with a disruptive and abusive senior faculty member, which blew up over the treatment of a graduate student. I had to take care of this issue, which resulted in protection of the student and the transfer of the professor to the north campus, and he soon retired. Some of the elements of the M.S. program, as the core beginning course, Introduction to Biological Research, also became an important feature of our Ph.D. program. The size of our M.S. program, and the growing quality of students (as well as the need for graduate teaching assistants to serve our expanding undergraduate population) led to our development of a Ph.D. program. At first, it was to be a cooperative program between us, FAU and the University of Central Florida (UCF) in Orlando. However, a very strong external review mandated by the Board of Regents gave us the opportunity to push through an independent Ph.D. program in 1989; I also served on the Graduate Committee at that time.

I had been interested in environmental issues since my days as a graduate student, increased by what I learned in living and travelling overseas, and by my brief teaching position at Upsala College. FIU had offered B.A. and B.S. degrees in Environmental Studies since opening in 1972. Ironically, it was one of the oldest such programs in the country in one of its youngest universities. Its director and cheerleader was Jack Parker, and he was aided by the Environmental Council, a group of individuals with environmental interests in various departments, as Philosophy, Economics, Political Science and International Relations. I became a member and enjoyed the interactions with those people.

In addition to dealing with program issues, the Council had also supported the maintenance of the Environmental Preserve, since its establishment in 1978. I became particularly concerned with the Preserve, along with Jack, and had to defend/protect it from development on numerous occasions. I became good friends with Charlie Hennington, the Grounds Superintendent, from the beginning of my work at FIU. Charlie understood the value of the university landscape for teaching, and was always looking for opportunities to plant unusual natives and interesting tropical plants. I was asked by the Campus Architect to serve as the chairperson of a new committee, the Landscape Advisory Committee, which advised on the master planning process and on landscape plans for new building projects. That committee then became the first Environmental Committee, later banished by a vice-president, and then re-established. I had to stick my neck out on many an occasion to uphold environmental values on campus, and received a University Service Award in 1991 for my environmental work. In the late 1990s the Preserve was threatened again, and I organized a charrette for the proper development of the area, the first such design activity on campus involving faculty, staff, students and outside professionals. The results of that chrarette are still being used to guide development of that part of the campus.

I was asked by the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences to lead a review of the Environmental studies program around 1993. The committee recommended that the program become a free-standing department, and the Dean concurred. In 1995, I became the first Chairperson of the new department, helping it to add faculty and eventually finding a physical home for it. I am reminded of the ground-breaking work David Fairbrothers was doing at that time, in preserving natural areas in New Jersey, and helping with the establishment of the Pinelands National Preserve. My service was tiny compared to that. I also remember that David was supportive of athletics, being a good personal friend of the football coach. I also became active in athletics, being appointed to the Athletic Council and serving for some time. Later, I became a vocal critic of the campaign to start a football team, and was a faculty leader in trying to reign in some abuses of the administration with regard to sports.

I also served as Chairperson of the Department of Biological Sciences for a year, not long before my retirement. That term was cut short when I took up another service responsibility as Director of the Kampong, of the National Tropical Botanical Garden, mainly based in Hawaii but with a garden in Miami, the historically important Kampong--the old home of the great plant explorer David Fairchild. I pushed for a close relationship with FIU, to give the garden more of an academic/scientific mission. As I write this, those plans are being realized.

The Lee family at our home in Miami, winter of 2012. Left to right: son Sylvan, David, Carol, daughter Katy, grandson Shaun.

I feel some satisfaction in serving a university that is so vital to the well-being of this area, with its problems and opportunities. Now, FIU is a university approaching 50,000 students, with professional schools of Law and Architecture, a full Engineering College and a new Medical School (which I helped as chairperson by serving on organizing committees).